Our Work

Broadening Our Understanding of Disability Rights

From legal compliance to respecting dignity

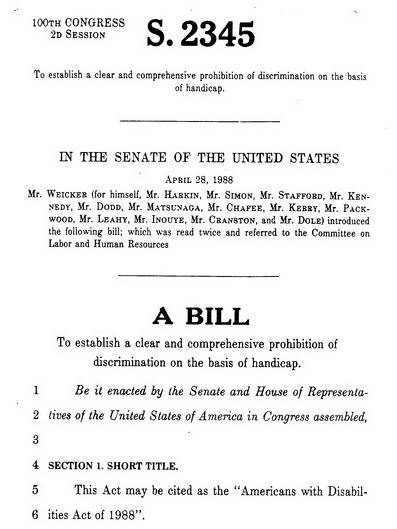

Since 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) has helped to expand people with disabilities' access to public spaces and their communities. But ADA compliance alone is unlikely to honor the deeper dignity interests recognized in the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) has been transformational in many ways, especially in the way that people with disabilities can access public spaces and thereby participate in their communities. Nevertheless, more than 30 years after the ADA's enactment, not that much has not changed. As HPOD Executive Director Professor Michael Ashley Stein and disability rights attorney Daniel Goldstein wrote for the Harvard Law Review Blog, the needle on unemployment of employable persons with disabilities has scarcely budged. In other areas things are getting worse. WebAim’s survey of the home pages of the one million most popular websites, for example, revealed barriers on 98.1% in 2020, an increased incidence rate from 97.8% in 2019; likewise, the average number of accessibility errors per home page rose to 60.9% in 2020 from 58.8% in 2019.

Stein and Goldstein argue that the time may have come "to consider how to move from [ADA] compliance as an imposition toward desired inclusion and belonging—from a semi-effective external enforcement stick to a more effective self-motivated carrot." From that perspective, current U.S. laws are not much help. Despite ample regulations under the ADA and related federal laws, aside from the notable exception of the ADA Architectural Guidelines (ADAAG) and the Rehabilitation Act’s 508 regulations, there is little in the way of guidance as to the affirmative steps that organizations could take to be inclusive and accessible to customers, employees, and job applicants with disabilities. And compliance with the ADAAG aside, compliance with 508 has been rare. Prominent examples include the extensive use of Google Docs before it was accessible and use of inaccessible Microsoft SharePoint by governmental entities at all levels.

Lessons from abroad may shed some light on the limits of compliance. For example, the Supreme Court of India issued a sweeping affirmation of persons with disabilities’ right to live in the world in Vikash Kumar v. Union Public Service Commission. In construing India’s 2016 Rights of Persons with Disabilities (RPwD) Act, the Court emphatically reframed an individual's perfunctory request for test-taking accommodations as a waystation in the disability community’s “continuing quest for dignity." The Kumar Court evocatively captured the RPwD Act’s ambitious vision: “The Act tells [persons with disabilities] that they belong, that they matter, that they are assets, not liabilities and that they make us stronger, not weaker.” Hence, the RPwD Act “travels beyond being merely a charter of non-discrimination […] by imposing a positive obligation on the State to secure the realization of rights.” Indeed, “[e]quality, non-discrimination and dignity are the essence of the protective ambit of the RPwD Act.”

By contrast, not once in its three decades of jurisprudence on the 1990 ADA has the U.S. Supreme Court similarly affirmed persons with disabilities’ right to live in the world. Indeed, the few ADA victories at the Court are more notable for their restraint than their expansiveness. The U.S. Supreme Court’s comparatively constrained jurisprudence may be traceable to limitations in the ADA itself that the RPwD Act avoids. For example, the RPwD Act focuses on accommodating all persons with disabilities in ways that the ADA does not. The ADA’s mandated accommodations are limited to a “qualified individual” with disability, which includes only those who would be capable of performing “essential functions” of a job and those who would meet “essential eligibility requirements” for participating in programs or activities if they are provided reasonable accommodations or auxiliary aids and services.

Although Kumar alludes to the ADA several times, Professor Stein and HPOD Director of Advocacy Initiatives Hezzy Smith believe it exceeded the U.S. Supreme Court’s approach to the ADA in large part due to its critical insight that the appellant’s accommodation request was part of a larger quest for dignity. Much like the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which references dignity 22 times, the RPwD Act includes it among its general principles. Arguably, dignity imbues everyday disability rights disputes with deeper import and urgency. Thus, the Kumar Court was able to connect the government’s duty to accommodate with the larger goal of “ensur[ing] that persons with disabilities are able to live a life of equality and dignity based on respect in society for their bodily and mental integrity.”

Such subtle attitudinal and normative shifts may signal the kind of shift that Stein and Goldstein describe, namely from narrow legal compliance to sincere respect for the inherent dignity of persons with disabilities' right to belong in the world.